|

|

| Musical Musings: Lent |

When I Survey the Wondrous Crossby Father Alfred McBride, O.Praem.This article appeared in the April 2, 1994 edition of Catholic Heritage magazine, formerly published by Our Sunday Visitor, Inc. The magazine is no longer being published. Over the century, artistic representations of the cross have changed considerably Several years ago, on a trip to Istanbul, Turkey, I met Metropolitan Bartholomew, who [was] ecumenical patriarch of the Orthodox Church. He invited me to their liturgy for the feast of the Triumph of the Cross on September 14. Fortunately, I was free and able to accept his offer. Midway through the service, a priest carried a large silver basin filled with aromatic leaves to the altar. Patriarch Demetrius blessed the leaves with water and incense.

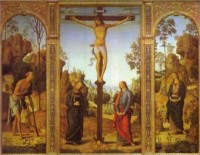

At the conclusion of the liturgy, I joined the patriarch in a procession to the altar where we kissed a cross held by the patriarch, who then gave each of us a sprig from the basin. I was told afterward that the leaves were sweet basil, from a custom which dates from Saint Helena's discovery of the True Cross in Jerusalem in 326. Legend says she found the hill of Calvary carpeted with basil plants. The experience remined me of my early days teaching religion in Saint Norbert High School, DePere, Wisconson. I wanted to give my students a vivid impression of what Jesus endured on the cross. The Gospel writers said little, just noting a few facts about the Crucifixion and adding the scene of the resurrected Jesus asking Thomas to touch the nail marks in His hands and the spear wound in His side. It was just at that time in the mid-1950s that a French doctor, Pierre Barbet, published his powerful study of the Passion, "A Doctor at Calvary." He analyzed the crucified figure on the Shroud of Turin with the eyes of a surgeon. With a physician's perspective, he gathered data from archeology and history to reconstruct a "medical examiner's report" on the scourging, crowning and crucifixion of Jesus. I learned that Jesus carried only the crossbar to the execution mound just outside Jerusalem's walls; the 10-foot vertical post was already there. Barbet argued that the nails were put behind the wristbone rather than in the palms of Christ's hands, because the palms could not have supported His weight. He stated that crucified victims could live as much as a week. They did not die from the nailing as from asphyxiation due to their inability to breathe properly, being progressively unable to lift themselves up for this purpose. Loss of blood and dehydration, caused by excessive beatings and stress, hastened Jesus' death, which occured in a few hours. Because the cross was virtually at eye level, the victims could converse with their families. Hence, the traditional Seven Last Words of Christ from the cross make more sense as part of His dialogue with the bystanders, His mother, John and the Good Thief. My students found Barbet's medical analysis absorbing. I was then able to move from the physical picture to the spiritual meaning of the cross and our salvation from sin. Soon after that, I made a retreat with Msgr. Martin Hellriegel, a Saint Louis priest and a pioneer in the American liturgical movement. I was startled by a comment he made that the early Christians did not make crucifixes because the sight caused them so much shame and horror. I needed to remember that they still witnessed such cruelties and were themselves subjected to the atrocities in the Roman amphitheaters. Msgr. Hellriegel emphasized that the early Christians did have what he called the Crux gemmata, the "Jeweled Cross," without the figure of the crucified Jesus. This drew their attention to the Easter Christ, the victorious Lord of the Resurrection, whose victory over sin, suffering and death served as the ideal model for them to follow. The first evidence of what would become the crucifix — the body of Jesus affixed to the cross — occurred between the sixth and ninth centuries. In the Middle Ages, the artistic representations of the cross traveled far from the Easter triumph of the Crux gemmata to the realistic portrayals of the agonized Jesus of the Passion. A thousand years after Calvary, Christians no longer knew what real crucifixions were like, so their imaginations required realistic representations of what they must have been like. The flowering of three-dimensional art and the taste for realistic portrayal had their effect on the appearance of a crucifix. Religious devotion that was centered on the crucifix became very popular. This is a compelling reason for the prevalence of the crucifix in medieval times. Saint Francis of Assisi understood this spiritual hunger and fostered the growth of what we know as the Stations of the Cross. Religious drama in the medieval mystery plays — which focused on the life, death and resurrection of Christ — accentuated this development, serving as a powerful form of catechesis for an oral, unlettered culture. Some parts of old Catholic Europe still preserve these customs — above all, in the solemn Holy Week parades attended by thousands in Seville, Spain. The role of the Blessed Mother in Crucifixion scenes underwent similar changes. In the early periods, Mary stands erect and contemplative at the foot of the cross. But as Jesus assumes a more tortured, so does Mary. By the late Middle Ages, Mary is now the Mother of Sorrows, the mourning mother, bent over with grief and tears and help up by Saint Mary Magdalene and the other women at the cross. Is is this Mary who is commemorated in the stirring Medieval Latin poem, Stabat mater ("The Mother Was Standing,") so often set to magnificent music, such as that by Monteverdi. It was the crushing impact of the Black Death (1350-1400) that brought these grief-laden depictions of the cross to their most wrenching stages. For fifty years, the plague threatened to destroy Europe and Christendom itself. In a sense, people needed to see that Jesus had suffered as much on Calvary as they were suffering now. Paradoxically, this gave them hope in the midst of tears. The suffering God made human pain bearable.

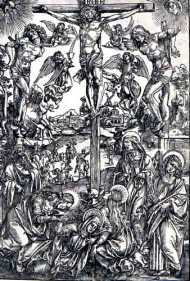

"Plague crosses," as they were called, appeared everywhere, and Albrecht Dürer's woodprints of these crosses remain as imperishable works of art. The modern Swedish filmmaker Ingmar Bergman returned to this period for his extraordinary movie "The Seventh Seal." He believed that many people in the modern world experience the same kind of "silence of God" that occurred in the late Middle Ages. Regardless of the truth of his position, his film shows how art attempts to capture the mood of a culture, which is what Dürer and others did with the cross. In the Reformation and Counter-Reformation, it was music more than anything else that revived the glory of the cross and its power of salvation. Johann Sebastian Bach's "Passion according to Saint Matthew" and Handel's "Messiah" recovered the splendor of Christ's majestic saving work in His cross and resurrection.

|