|

| Musical Musings: Liturgy |

|

|

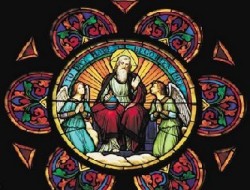

Revised Roman Missal: Understanding the reasons for the changes - Part 2How and why the Church is improving the English translation of The Roman MissalConsubstantialemThis article is reprinted from OSV Newsweekly, a publication of Our Sunday Visitor, Inc, with the kind permission of the editor, John Norton, and author / contributing editor, Emily Stimpson. The Mass, for as poetic as it can sound, is no Broadway tune. The words it contains aren't there for their rhyming potential. They're there because they mean something, because they say something true and important about God, the world and the human condition. So, what are some of the changes Catholics will encounter starting on November 27, the first Sunday of Advent, that seem small but are actually quite significant? ConsubstantialemNow we say, "One in being with the Father" during the Nicene Creed. Beginning November 27, we'll say, "Consubstantial with the Father." Here's why:

Arius' bishop, Alexander, however, said otherwise. Siding with the pope and the majority of Catholic bishops, he defended the teaching that the Father and Son were of the same substance, or homoousios. He also defended the belief that the Father and Son were co-eternal, that they had existed together through all eternity. One "iota" (the Greek letter "i") was all that differentiated homoiousios from homoousios. But for that "iota" Catholics gave their lives, and bishops such as Saint Athanasius and Saint Hilary of Poitiers were sent into exile (Athanasius no fewer than five times). In 325, however, the Council of Nicaea definitively settled the question, declaring the Father and Son were of the same substance, homoousios. In the Latin version of the creed that bears the council's name [Nicene], which enshrined the correct definition of the relationship between the Father and the Son, the Church Fathers translated the Greek homoousios into the Latin consubstantialem. The English translation of consubstantialem is the nearly identical "consubstantial," and in the English translations of the Creed that preceded the 1970 translation, "consubstantial" was the word most often used. But with the introduction of the Pauline Mass in 1970, "consubstantial" was dropped from the Creed. In its place was the phrase, "one in being." The substitution was made for simplicity's sake. "One in being" seemed more understandable and accessible than "consubstantial." Which to an extent it was. But only to an extent. Which is why, when the new translation of the Roman Missal goes into effect next Advent, "consubstantial" will return to its traditional place in the Nicene Creed. The reason for that switch is much the same as the reason homoousios trumped homoiousios in 325. It more accurately describes the relationship between God the Father and God the Son. "'One in being' is vague and open to misinterpretation," said Father Roy, who teaches liturgy at the University of Notre Dame. "The Father is the source of all being. He is the sole Being whose essence is his existence, and he gives all of us our being and existence. So, to a certain extent, we're all 'one in being' with the Father. That doesn't say anything unique about Christ." Moreover, added Father Stravinskas, author and liturgist, "Just because 'one in being' is three simple words in a row doesn't mean that the average person understands what the phrase means." "In fact," he continued, "many don't. The simplicity of the phrase is deceptive. It rolls off the tongue without ever forcing people to stop and think about what they're saying." But what they're saying is something that has to be thought about — deeply thought about — to even remotely be understood. "When people first hear they'll be saying 'consubstantial,' their first response is, 'I don't know what that means. Why can't we use a word I understand?'" said Father Hilgartner, director of USCCB Secretariat for Divine Worship. "But we're talking about a mystery that no one fully understands and that can't be fully articulated. In some ways the use of the word helps us confront the mystery, to stand before the mystery." Joe Paprocki, from Loyola Press, agrees, seeing the word as a "catechetical moment" that can lead people to a deeper understanding of the Trinity. "People in centuries past have given their lives defending these words," he said. "Words are crucial. And this word, consubstantial, is crucial to helping us understand the relationship between the Father and the Son. If the word causes some head scratching, that's OK, as long as that head scratching leads to people asking what the word means and why it's important."

Copyright © 2011 by Our Sunday Visitor, Inc. |

Submit Your Music / Contact Us / Company Description / Links

Seventeen hundred years ago, the Catholic Church was drawn into a knockdown, drag-out fight about how to best express the relationship between God the Father and God the Son.

The fight was sparked by the Alexandrian priest Arius.

He and his followers, dubbed Arians, argued that the Father and Son were of like substance, homoiousios, but that the Son had not always been with the Father, that the Father had in fact pre-existed the Son.

Seventeen hundred years ago, the Catholic Church was drawn into a knockdown, drag-out fight about how to best express the relationship between God the Father and God the Son.

The fight was sparked by the Alexandrian priest Arius.

He and his followers, dubbed Arians, argued that the Father and Son were of like substance, homoiousios, but that the Son had not always been with the Father, that the Father had in fact pre-existed the Son.