|

|

| Musical Musings: Miscellaneous |

The Heroic Task of ChantingThis article appeared in the Winter 2008 edition of Sacred Music journal, published by the Church Music Association of America. It is reprinted with the kind permission of Jeffrey Tucker, Managing Editor & Author.

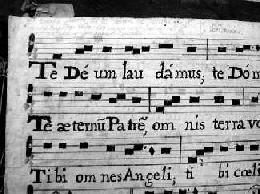

The style is unknown in today's popular culture. The notation is usually not taught in music classes in most high school or college settings. The language is neither a living vernacular nor a familiar liturgical one. Even experienced singers can look at a page of chant and find themselves unable to know what the tune should sound like or how it should be interpreted. But they forge ahead in any case. They buy books, study the tutorials, attend colloquia, read the forums and post on them, join email lists, share recordings, gather with others as often as possible, surround themselves with pronunciation guides, learn the musical language of solfege, all in what is really a heroic effort to make something that had been all-but-banished from our Catholc culture heard and internalized again in our times. I'm struck by this remarkable fact in light of an experience we had a few weeks ago. Our schola was preparing to sing Te Deum for a special parish event. The chant is very long. The language is quite difficult. Intonations problems are endemic. The rhythm of the piece calls on every skill that chant requires, and the style must be free and familiar, or else it just won't sound like Te Deum. This piece ranks among the greatest and oldest and most persistent of all Christian hymns, and it can't be sung with caution and shyness. It has to be sung as if it has been sung for all time. Working off and on with this piece, in scattered rehearsals whenever there was time remaining when other demands weren't pressing, we would keep plugging away. Our schola director would have us speak the words, then sing the piece on one tone, alternating between high and low voices. We would focus on particular spots and iron out pitch and language problems when they appeared. It took us the better part of a year working at this pace, two steps forward and one step back, but it finally happened. At the end, the piece began to seem joyful, effortless, inevitable. Then we had some outside singers join us for the event for which this was being sung. They were from the local Baptist, Presbyterian, and Unitarian churches. We only had an hour to rehearse all the music, which left about twenty minutes for Te Deum, sight-reading. They stood among twelve singers who knew the piece perfectly. In twenty minutes time, they were up to speed on the chant: the words, tune, and style. They were impressed at how much easier chant was to sing than they thought. In the performance, all the new singers did a wonderful job! So how is it that our schola took nearly a year to learn this, while the new singers took only twenty minutes? If you have ever sung in a choir, you know why. Singing with people who already know a piece requires only that you attach your voice to theirs and move forward. On parts on which you are unsure, you can back away, and hearing the correct version next to you means that you can fix it the next time through. The difference is immense. The first singers to confront unfamilar chant are like people facing a forest of trees and a thicket of brush who are attempting to make a new trail with machetes and their own feet. Those who come along later to take the same route need merely to walk on the trail already made for them. The difference is substantial. In most past Christian generations, the trail was already there, and one generation rolled into the next so that most singers were in the position of those visiting singers on the day we sang Te Deum. From the seventh or eighth century forward, singers fit into a structure of something that was already there. Not that chant was sung in every parish or every cathedral, but the sound and feel — if not the tunes themselves — were part of what it meant to be Catholic. The music was in the air. Scholas still had to work hard but they didn't have to blaze completely new trails. Even in modern pre-conciliar times where the chant was not sung, there were copies of the Liber usualis around and priests who knew the chant, and always some parishioners who had a sense of it. In the best situations of the past, new singers were always in the minority among experienced singers, and they fit into an existing ensemble. What singers confront today is something incredibly daunting and probably nearly unprecedented. They are conjuring up a two-millennium-long tradition that was abruptly stopped for several generations and trying to make it live again. To do this is roughly akin to a scene from a dystopian novel in which it falls to a few to reinvent electricity or make clothes from cotton and wool for the first time. It is a heroic effort, something far harder for us than for most any Christian singers in the past. I can recall only several years ago standing in a rehearsal room staring at a complicated chant and trying to make it work note by note. It took me up to an hour to become familiar with a new chant and even then I would sometimes get on the wrong track and sing a wrong note again and again. It would take someone else from our schola to correct the mistake and make it right. We discover from these experiences that learning chant from scratch requires both private study and group effort. We have to learn to sing on our own and then we must also learn to sing with a group in which we all teach each other. You find very early on that recordings are helpful but they only get you a little of the way there. Ultimately you have to learn to render it on your own and experience the chant physically within your own voice, ideally standing next to a person who knows it well. But that person isn't around, so you have to conjure up the entire piece on your own. There is no shortcut. This is the great difficulty of the chant. It is not so much the chant itself but its novelty that makes its re-creation so daunting. The chant is not intended to be novelty. It is a tradition that is supposed to be continuous from age to age, entrenching itself ever deeper into the culture and inspiring every form of elaboration. It never should have been abandoned, especially not after a church council that conferred on the chant primacy of place in the Roman Rite. But it is a fact that the existing generation must deal with and overcome, carrying the tradition to the future. This is one reason the CMAA published the Parish Book of Chant: to make this music accessible in every possible way. And that is only the singing part. There are parish politics to deal with, the remarkably fast pace of the liturgical year, and celebrants to persuade. Even given all the barriers, today's scholas press onward. For this reason, this generation of chanters really does deserve the title heroic. The challenges they face and the tradition they rescue will surely be recorded in the annals of the history of liturgical art. It is often said that these challenges are too much, that we can't expect regular musicians in parishes to take them on, especially given the low pay and extreme time demands. On the contrary, the rewards of singing sacred music, of becoming part of the liturgical structure of the Mass itself, are immense. Yes, it does require work and time, but this is what is asked of us for the highest privilege a musician can be given. It is not a burden but rather an inspiration, one that humbles all of us. |

Today's Gregorian scholas, mostly founded within the last serveral years, and almost entirely consisting of non-professional singers, face a task unlike most any in any previous age.

They confront the largest single reserve of music of a certain type and are determined to make it live again in liturgy.

Today's Gregorian scholas, mostly founded within the last serveral years, and almost entirely consisting of non-professional singers, face a task unlike most any in any previous age.

They confront the largest single reserve of music of a certain type and are determined to make it live again in liturgy.