|

|

| Musical Musings: |

|

|

Is Gregorian Chant Pastoral?This article is reprinted from the blog, The Chant Café, by Jeffrey Tucker

To be sure, this is not entirely what people might have expected. The usual fare is a familiar carol, perhaps gussied up with trumpets and flutes and various other things played by the musicians who mysteriously emerge to be featured at these splashy holiday events, and then vanish once it is over. This did not happen this Christmas. Instead, what the people heard was woven into the fabric of the Mass as thoroughly as the celebrant's part. And just as the people do not say everything with the celebrant, they did not sing with the schola; they stood and listened instead. But did they participate? Most certainly. The environment and the music itself nearly compels it. How so? A floating chant this beautiful, and yet strangely minimalist in this world filled with incredible noise and racket at every turn, does not provide the complete experience with its notes or words alone. It is so pure, so comparatively sparse, even stark, but full of movement, and where? It is moving toward something and upwards to something not found outside these walls. The chant's very remoteness elicits something from within us, drawing on our hearts and minds and asking us to provide something to complete the picture. And what is that something? It is a prayer. That prayer can be for something very personal, for something or someone that has been causing us pain. It could be about terrible things we've done or opportunities we've missed to do good. It could be a prayer of thanks for the wonderful blessings that surround us. It might be even more vague: perhaps just a sense of having some connection to the transcendent for the first time in a very long time. It gives us a sense of peace and safety even in times of turmoil. The chant lasts a surprisingly long period of time, but somehow not long enough, because this peace we feel is luxurious. It feels right, perhaps not at first, but after a few minutes as time itself begins to fade in importance. The discomfort we felt at the outset, when we heard those initial notes that seemed so isolated, has given way to comfort and a realization that we are surrounded. We are now used to the sound of still voices singing one line and we realize that there is only one place and one activity that provides us with this sense of transcendence. We have entered the presence of holy things. God is with us. Christmas is not just a history; it is a reality and this reality is being lived in the liturgy. We don't sing chant only because it is what is being asked of us; we sing chant because the liturgy loves it and the faith loves it and because it is, speaking from the purely pastoral point of view, exactly what we need and want. Hearing it and experiencing it is a challenge and it does ask something from everyone; and that something is the humility to listen to the Word and to dare to allow our hearts to be changed. See: |

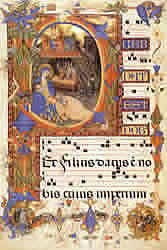

At Christmas morning Mass, at a very mainstream parish packed with visitors from all places around the country, the entrance song was Puer natus est, from the

At Christmas morning Mass, at a very mainstream parish packed with visitors from all places around the country, the entrance song was Puer natus est, from the