|

| Musical Musings: Miscellaneous |

|

|

Benedict XVI on Music

In his remarks, Benedict XVI presented some personal thoughts on music and sacred music. He commended his predecessor, Saint John Paul II, "because without him, my spiritual and theological journey would not have even been imaginable. With his brilliant example he also showed us how the joy of great sacred music and the task of common participation in the sacred liturgy, the solemn joy and the simplicity of the humble celebration of the faith can go hand in hand." Having grown up in a tradition that fully supported Sunday Masses accompanied by choir and orchestra, he remarked about one Mass in particular. "Indelibly impressed in my memory, for instance, is how, when the first notes of Mozart's Coronation Mass sounded, Heaven virtually opened and the presence of the Lord was experienced very profoundly." He embraced the Liturgical Movement in Bavaria, but noticed that "little by little the tension became perceptible between the participatio actuosa in keeping with the liturgy and the solemn music that enveloped the sacred action, even if it was not yet perceived so strong." Written very clearly in the Constitution on the Liturgy of Vatican Council II is that "The patrimony of sacred music be preserved and incremented with great care" (1124). On the other hand, the text evidences, as a fundamental liturgical category, the participatio actuosa of all the faithful in the sacred action. What in the Constitution was still peacefully together, subsequently, in the reception of the Council was often in a relation of dramatic tension. Significant environments of the Liturgical Movement held that, for the great choral works and even for the Masses for orchestra there would be room in the future only in concert halls, not in the liturgy. Here there could be a place only for the common singing and prayer of the faithful. On the other hand, there was consternation over the cultural impoverishment of the Church, which would necessarily flow from this. In what way could both things be reconciled? How could the Council be implemented in its entirety? These were the questions posed to me and to many other faithful, to simple people as well as to persons in possession of theological formation. The pope emeritus mentioned three places from which music emanates:

Benedict spoke of the realm of music in cultures and religions.

Present in the scope of the different cultures and religions is great literature, great architecture, great painting and great sculptures.

And everywhere there is also music.

And yet in no other cultural domain is there music of equal grandeur to that born in the sphere of the Christian faith: from Palestrina to Bach, to Handel, up to Mozart, Beethoven and Bruckner.

Western music is something unique, which has no equal in other cultures. And this — it seems to me — should make us think.

Article written 14 July 2015 The speech was delivered in Italian. The English quotes herein are from an article on ZENIT |

Submit Your Music / Contact Us / Company Description / Links

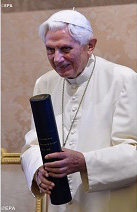

On 04 July 2015, Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI received two Doctorates honoris causa from the John Paul II Pontifical University of Krakow and from the Academy of Music of Krakow, Poland.

They were conferred by His Eminence, Stanislaw Cardinal Dziwisz, Archbishop of Krakow, at a ceremony at Castel Gandolfo, where the pope emeritus was spending a few weeks at the traditional papal summer residence.

On 04 July 2015, Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI received two Doctorates honoris causa from the John Paul II Pontifical University of Krakow and from the Academy of Music of Krakow, Poland.

They were conferred by His Eminence, Stanislaw Cardinal Dziwisz, Archbishop of Krakow, at a ceremony at Castel Gandolfo, where the pope emeritus was spending a few weeks at the traditional papal summer residence.