|

| Musical Musings: Miscellaneous |

|

|

Taking up the PsalterThis article is reprinted from the April 2010 issue of Adoremus Bulletin, with the kind permission of then editor, Helen Hull Hitchcock. Recently I was asked by some friends who are not accustomed to using the Psalter, why it might be to their advantage to take it up in their worship and private devotion. This should not be too difficult a matter to explain, I thought at first. Anyone who has listened to Handel's Messiah is aware of the long Christian tradition of reading the Old Testament as a book of prophecy about Christ. Surely this would be a good place to start. Christ in the PsalmsHaving studied the history of Christian worship and prayer, I knew well the tradition that sang the psalms in praise of the Royal Son of David, the Lord Jesus Christ (e.g. Psalms 2, 110, 132), upon whom had been poured the oil of gladness (Ps 45:8).1 How the heart thrills when the Messianic Psalms are sung, especially during Advent and Christmastide! In the psalms of trouble and suffering, who could not help but recognize Jesus, the Suffering Servant? On the Cross, the Psalms of His People provided the words He needed to cry out to His God: My God, my God, why have you forsaken me? (Ps 22) — and led Him to commend His life and labors into the hands of the Father: Into your hands I commend my spirit. (Ps 31:6).2 No wonder these psalms occur so often during Lent and Holy Week. And then, how to hymn His resurrection glory? No finer song than Psalm 118 for praising the stone rejected become the cornerstone, and celebrating every Sunday as the special day made by the Lord, on which rejoicing and gladness are the order of the day (Ps 118:24; see also Mt 21:42, Mk 12:10 and Lk 20:17; cf. Acts 4:11 and I Pt 2:7). Although He did return to the Father's glory and is now seated at God's right hand, Jesus did not forget the loved ones who remained behind. The gift of the Holy Spirit in wind and fire at Pentecost attested: I am with you evermore. Psalter in hand, our Christian ancestors took up the chant on Ascension Day, God goes up with shouts of joy (Ps 47:6). and longed for His Spirit-gift in their own lives, praying, Send forth your Spirit … renew the face of the earth! (Ps 104:30).3 Baptism and the Lord's SupperAs I was mulling over these, and various other possible ways of responding to the request my friends had made, I noticed, stacked in the corner of my bookcase, some postcards, memories of student years in Rome. Among them I came across one of the ancient baptistries of the city, its walls adorned with dazzling mosaics. There, on the wall opposite the baptismal pool, situated in such a way that, as the newly baptized emerged dripping from the waters, their eyes would immediately fall upon it, was the figure of a youthful shepherd boy. A little lamb was hoisted upon his broad shoulders. I must show this to my friends and tell them how those early Christians newly up from the waters, upon seeing this wonderful work of art, would remember that it was Jesus who had assured them, I am the good shepherd (Jn 10:11), and would sing of Him to whom their lives were now irrevocably committed:

The Lord is my shepherd … I picked up another postcard. This time the scene, from the catacombs, was that of a tiny cavern deep under the street level. Perhaps at one time it had been used as a small chapel. Etched on one of its walls, in red the color of clay, was a small altar. Near it were fish, and two baskets filled with loaves marked with crosses. Vines heavy with clusters of ripe grapes were also near. All was ready for a sacred meal. Taste and see that the Lord is good! (Ps 34:9, cf. I Pt 2:3). Perhaps my friends would be interested to know that primitive Christians found in this psalm words most suitable to celebrate Christ present among them as they shard the Bread of Angels (Ps 78:25) and the Chalice of Salvation (Ps 116:3). Perhaps this traditional Communion psalm would find a place in their own commemoration of the Lord's Supper. The Mirror Image of LifeAs I considered the matter, I felt sure that these points would be helpful to my friends. And yet, something more was needed. What was it? I began paging through the hymnal they used, and as I did so, it became more and more evident what had to be said about the advantage of the Psalter. This is what I noticed. Like the Psalter, the hymnal contained numerous hymns that praised and thanked God, and many others that recalled the beauty of His creation and extolled His unceasing providence. Faith and hope in His promises were duly expressed, and the fellowship of Christian believers extolled. Hymns celebrating the mystery of Christ in the Church Year were not lacking either. Indeed, a number of them were beautiful paraphrases of the great Christological Psalms. Unlike the Psalter, however, there was not one angry hymn in the entire collection. So often we feel the need to pour out our rage to God in prayer. How will the hymnal help us then? Perhaps this is precisely the point at which the Psalter is most valuable for our needs today, and the point at which our current worship books and hymnals fall short. The Psalter is true to life; it accords so accurately with the rawness of human experience. It leaves nothing unsaid, no emotion unexpressed. I knew then that I would have to tell my friends the whole truth about the Psalter, and what might happen to them if they took it up. First of all, the psalms would expose the pain of living, and demand that they face squarely every condition of human suffering. Betrayal by friends (Ps 55), attacks of enemies (Ps 56), the unfairness of a world in which the wicked seem to get rewards, and the just, for all their devoted piety, seem afflicted with endless trouble (Ps 73) — it is all there, in graphic detail. The ultimate issues of sickness and death receive particular attention:

Spent and utterly crushed,

You have given me a short span of days;

Take away your scourge from me. This sort of prayer disorients life. It threatens security. It hurts! We are frightened. But it would not be enough merely to expose pain. More is needed. There must also be a response on the part of the believing heart. It must do something with this pain. It must present it to God! Hear my voice, O God, as I complain! (Ps 64:1). These words were frequently to be found on the lips of some of the greatest saints! Curses, complaints nad laments abound in the Psalter. And this is good. Taking up the Psalter makes a bold statement to the world about the relationship between God and the human family. God cares about everything that is happening in our lives. He cares about all our experiences, especially those we find difficult and confusing. Since the Psalter is His inspired word, it is clear that He expects to hear from us when we are fed up with the disappoinment and suffering of life. Even when we are fed up with God! Taking up the Psalter makes a bold statement about us. When we sincerely join the prayer of our hearts to the words of our lips, we declare that we have finally decided to stop burying pain deep within, where neither God nor loved ones can reach to help us. We say that we are ready to suffer through our pain and, when the time comes, to get over it and let it go. Taking up the Psalter holds a promise. Disorientation is not forever:

When I think: "I have lost my foothold," We are not alone in our trouble; suffering, sickness and death do not have the final say. Could this be the reason why so many Christians have clung tenaciously to the Psalter for so many centuries? We need desparately to listen to the psalms, to read them and to sing them, alone and together. To scream, to delight, to weep, to pray them again and again until

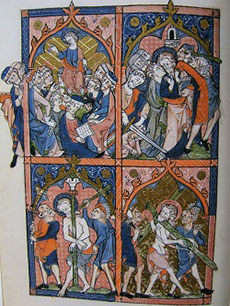

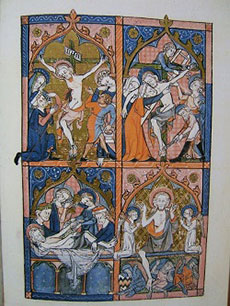

My body and my heart faint for joy; I know how I will answer my friends. I will tell them, "If you take up the Psalter, prepare for an ordeal. Get ready to see the mirror image of your own life in the book your hands hold. Prepare to let the tears flow … and the sighs, and the groans. And that will be good." The Passion of Christ from the Ramsey PsalterIlluminated manuscript, Ramsey Abbey, England, circa 1300-1310. (New York, Pierpont Morgan Library)

The Ramsey Psalter was commissioned as a gift for the abbot, John de Sawtry, by Walter of Grafham, the abbey cellarer. The psalms are prefaced by ten pages of miniatures, including the illustrations of the Passion of Christ. On the left: Jesus is condemned, tormented, scouraged, forced to bear His cross. The sneering tormenters have twisted bodies and snout-like noses; two men at the lower left have wings attached to their heads, a medieval sign of evil. On the right, Jesus is crucified, taken from the cross, entombed; finally His resurrection is shown. End notes:

Article published April 2010 Copyright © 2009 Saint Meinrad Archabbey, Saint Meinrad, Indiana. |

Submit Your Music / Contact Us / Company Description / Links