|

|

| Musical Musings: Miscellaneous |

Gregorian Chant:Back to Basics in the Roman RiteThis article, which appeared in the June 2005 edition of The American Organist Magazine, is reprinted with the kind permission of the editor, Anthony Baglivi.

The Church acknowledges Gregorian chant as proper to the Roman liturgy; therefore, other things being equal, it should be given pride of place in liturgical services.

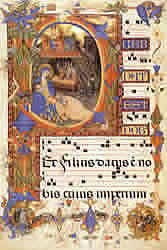

Why have Chant and its sequels captured so much attention? Many young people are asking where this beautiful music originated and how it came to be used in the Church. Gregorian chant has been sung in the Catholic Church for centuries. In fact, until the end of the Second Vatican Council in 1965, one could hear Gregorian chant on almost any given Sunday in any diocese in this country. In the space of just a few years, however, it seemed to have vanished. Where did it go, and why is chant so infrequently heard at the parish level today? Gregorian chant is unfamiliar to many people and should be listened to carefully. Aside from its intrinsic beauty, one should also appreciate its historical value and, more importantly, its liturgical value and purpose. In chant, the solemnity of the text is raised to an exalted level by being cantillated, or intoned, to a musical line. The rhythm of chant is free and is governed more by the rhythms of speech than by imposed musical patterns. The melody is indicated by small signs above the text, sometimes square or diamond-shaped notations called neumes, first written down in the tenth century. It was not until the end of the eleventh century that the pitches were accurately written using a system of letters. The first few chants of the Church were sung in Hebrew and then in Greek. A legend dating from the ninth century tells how Pope Saint Gregory I (590-604) compiled the body of plainchant. It is said that he carefully collected and wisely arranged music that had been handed down over the centuries. This music, called Gregorian chant, spread to all parts of Christian Europe and is still sung daily in many religious houses throughout the world. While it has been tradition to attach Gregory's name to chant, the available evidence does not support this. Apart from insufficient documentation, liturgical and musical analysis has found no strong evidence that the melodies first written down in the ninth century could be as old as Gregory. Nevertheless, we are certain that Pope Saint Gregory is responsible for assembling a liturgical book (antiphonus cento), and also for protecting the purity and integrity of sacred chant by prescribing laws and regulations over it. Prayer, meditation, reverence, awe, and love — Gregorian chant carries them in rhythm and melody. More than any other music with lyrics, chant is "heightened speech." In chant the music and prose are perfectly integrated. Its function is to add solemnity to Christian worship. In sacred music, the text is at the heart of the composition. The chief duty of sacred music is to clothe the liturgical text so that it moves the faithful to devotion and prayer. Chant does this in a most splendid and reverent way. This becomes apparent while listening to a recording of the Vexilla regis or the Pange lingua. Sacred chant is a heightened form of prayer. Church musicians, liturgists, and the clergy should reflect on the reasons for the renewed interest in Gregorian chant, and what it means in terms of prayer and the evolution of liturgy. Possibly the renewed interest in chant reveals a desire to immerse oneself in a world of serenity and peace, away from the distractions of a hectic and sometimes discordant daily life. Hearing chant can be a moving experience, but how does one go about learning it? A quick review of the Church documents on sacred music provides guidance on how and when sacred chant may be sung during various parts of the Mass, the Liturgy of the Hours, and during other liturgies. The documents tell us what should be attained when we present music for divine worship; and chant is the supreme model the Church fathers encourage the faithful to use. IIIn the past 40 years, a variety of music has been tolerated in the Roman Church. Contemporary, folk, polka, country, and other forms of inappropriate secular music have infected the liturgies; and some of this music has also crept into our hymnals. In light of the instructions on sacred music from the Holy See, it is odd that non-sacred music continues to permeate our liturgies. Perhaps the bishops and pastors who abdicated their authority over these matters now need to correct them. It is difficult to believe that the Council Fathers and those responsible for the liturgical reforms 40 years ago, envisioned a total absence of Gregorian chant and Latin from the Order of the Mass. It is doubtful that today's liturgies are the intended product of the spirit or the intent of the Second Vatican Council. Still today, many Catholic musicians, liturgists, and the clergy are reluctant to embrace the timeless traditions of the Church and the directives of the Holy See. Gregorian chant, sacred polyphony, and the use of Latin in the Mass are frequently viewed as being incongruous with the liturgy, and are sometimes greeted with antipathy and even outright hostility at their mere suggestion. In 1947, Pius XII's encyclical, Mediator Dei, confirmed the norms established by Pius X (Motu proprio Tra le sollecitudini) and Pius XI regarding sacred music. Some 15 years later, the Second Vatican Council's document on the liturgy, Sacrosanctum concilium, reiterated and futher expanded the norms for sacred music. The new directives contained in the General Instruction on the Roman Missal provide instruction on the use of chant in the Mass. The reluctance on the part of the clergy and musicians to embrace Gregorian chant is very apparent. Perhaps the reason is that they [the clergy, musicians, and liturgists] are no longer trained in liturgy, sacred music, aesthetics, and the history of the Roman Rite. The last 40 years have left an indelible mark on our liturgies. It is a mark of confusion sprinkled with secularism and other agendas. Many of our liturgies have lost the sense of sacredness. The sense of awe and mystery formerly associated with the Mass is no longer present. For 40 years, the Catholic Church has experienced a tumultuous change in nearly every aspect of her liturgical and musical life. The Council Fathers wisely drafted instructions specifically designed to protect sacred tradition and the law. And the bishops, as caretakers of that tradition, in cooperation with the clergy and musicians as collaborators, should always strive to improve the quality of music used in the liturgies. More imporatantly, they should adhere to the Rite and what has been promulgated by the Holy See. Perhaps a Third Ecumenical Council is needed to correct some aspects in the Order of the Mass, our liturgies, and also redefine sacred music. Just as the clergy are obligated to follow the rubrics established by the Holy See, church musicians and liturgists should follow the directives regarding sacred music and liturgy. Sacred music needs to be clearly defined with guiding norms and discipline. This is best accomplished at the diocesan level. The cathedral should set the standard for the diocese. Improving the quality of the liturgies and music will occur when the bishops and pastors are willing to embrace the directives of the Holy See (Instruction Redemptionis Sacramentum, March 25, 2004). In retrospect, a number of outside factors influenced and perverted the intent and spirit of the Second Vatican Council. in many instances the wishes of the Council Fathers were ignored, and some documents may have been misinterpreted. |

In 1994, the Benedictine Monks of Santo Domingo de Silos in Spain released a recording entitled Chant.

To the astonishment of many, this seemingly esoteric offering climbed to the Top 5 on the U.S. pop charts.

A few years later, the monks released another recording for Christmas entitled Chant Noël. a collection of ancient Christmas music.

Chant II was then released in response to the popularity of the first recording.

In 1994, the Benedictine Monks of Santo Domingo de Silos in Spain released a recording entitled Chant.

To the astonishment of many, this seemingly esoteric offering climbed to the Top 5 on the U.S. pop charts.

A few years later, the monks released another recording for Christmas entitled Chant Noël. a collection of ancient Christmas music.

Chant II was then released in response to the popularity of the first recording.