|

|

| Musical Musings: Miscellaneous |

Is Chant for Everyone?Part 2This article appeared as the second half of the Commentary section in the Summer 2008 edition of Sacred Music journal, published by the Church Music Association of America. It is reprinted with the kind permission of the author, Jeffrey Tucker.

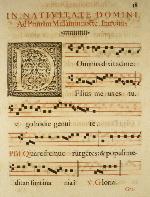

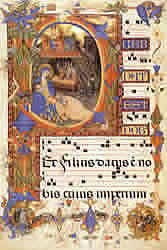

There is a sense in which, too, the chant does offer an appeal to those who find that modern life is too complicated and there is something to be gained by going back to the roots. It was, after all, Gregorian chant that gave rise to the first music schools, to notation, to harmonization, which led to Palestrina, Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, and onwards. With such a heritage, it is extremely important that the Catholic Church get it right, offering the highest art to the highest purpose, not only as a means of realizing the sacraments and communicating the Gospel but also as means of transmitting high art to the whole world. The right place to begin is the Graduale Romanum (the "Roman Gradual"). It is the official book of music for Mass. What appeared in 1908 was not actually the first edition but the restorative edition that presented the music of the Church for the first time without post-Trent corruptions and confusions. The Graduale was the great achievement of the monks of Solesmes, and an amazing gift to the faith and the world. It is still in use. It is still normative for the Mass. When Vatican II called the music of the Mass a "treasure of inestimable value" that is more precious than that of any other art, one that deserves primacy of place at liturgy, it was speaking specifically of the Graduale. The book is named for its most famous chant, which sets the psalm after the first reading to chant. But what it includes are all the chants for the Ordinary of the Mass: Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, Agnus. It also includes the Propers: Introit, Gradual, Alleluia or Tract, Offertory, Communion. The Sequences are here. Occasional hymns are here. In short, it contains the music that is bound up with the Mass itself. What's remarkable is that most Catholics have never heard of it. Perhaps more strikingly, most Catholic musicians have never heard of it. Herein lies a sad and tragic tale of missed opportunities, misinformation, and even disobedience. But amidst it all, there stands the Graduale with the greatest music ever assembled in one spot, ready for use at this Sunday's Mass. Can there be any doubt of its permanence and immanent return? I don't think so, not with a pope who is working hard toward that goal, not with chant workshops around the country filling up with eager students, not with the growing Catholic demand for seriousness and solemnity in liturgy. But there is more important consideration here. This music uniquely bears the marks of the Church. It is holy. It is universal. It is a unifying force. It grew up alongside the Mass with roots dating to the early Church. And as Pius X said of all sacred music, it is the archetype of what beautiful music should be. Its form is endlessly fascinating, to the point that any one chant of thousands can be examined in great detail to yield profound insights about our faith and liturgy. How did the modern Graduale come about? The work really began with the founding of the Solesmes monastery in France in the 1830s by Dom Guéranger. The bulk of the musical work was done by Dom Pothier, whose first treatises on chant appeared in the 1880s. Research and typography was further strengthened by Dom Mocquerreau. The goal was always the same: to clean the chant of the alterations and mutilations that had befallen it in the years following the Council of Trent, when less able hands were made responsible for preserving and protecting it from corruption. This required a fantastic amount of archival work and creativity. The Vatican became very interested in the work of Solesmes, and interested in producing an authoritative Vatican Gradual. Solesmes was charged with the task and the glorious book appeared in 1908. What followed was a remarkable revival of the chant, assisted greatly by the compilatation of chant that was known to all Catholic musicians before Vatican II: the Liber usualis. This book, though not an official book, contained most chants of the Graduale (1908) plus wonderful tutorials on singing the Mass, as well as many hymns, psalms, antiphons, and much more music for the Divine Office. By the time of Vatican II, the future of chant looked very bright indeed, with choir schools opening, new books appearing, and children's choirs booming in Catholic schools. It was at this point that the council enshrined the following words into liturgical law: "Other things being equal, Gregorian chant should be given a primary place in liturgical services." Chant had grown up alongside the Mass as the music of the Catholic Church but here was the first time a church council had spoken decisively on the issue. What followed was expected by very few. In a few short years, the entire infrastructure that had been developed in support of chant came crumbling down. Publishers collapsed. Choir directors were fired. Seminaries began to experiment with popular music at Mass. This became the fashion, and liturgy had succumbed to cultural pressures of the time, many of which are quite embarrassing in retrospect. This tendancy might have burnt itself out but for the introduction of the vernacular in Mass, which gave the impression that Latin was out completely and thus also was Gregorian chant. The new Mass was introduced in 1970. No one said anything about the Graduale no longer applying to it. Indeed, that would have been impossible. The Graduale was as much a part of the new Mass as the old. But because of the introduction of the vernacular, the change in the calendar, the new placement of the propers, and new texts introduced for spoken propers, as well as the general atmosphere of change, there was widespread confusion on this point. Simply put, hardly anyone was prepared to say what was true and what was not concerning music. A guide appeared but was largely ignored. It was fully four years before the Graduale Romanum appeared in a form that had been adapted to the new Mass. By that time, it seemed that hardly anyone cared anymore. The new music performed by new groups was the rage, and precious few kept the tradition going. That was then, and this is now. We've been through several waves of popular-selling chant CDs, with another on its way. The new U.S. bishops' letter on music (Sing to the Lord) highlights the pre-eminent role of chant at Mass. So does the General Instruction. It is being rediscovered by a new generation of priests. Chant scholas are being founded all over the country. Subscriptions to Sacred Music are at a thirty year high. The Church Music Association of America, the roots of which date to 1874, has experienced a revival. On this hundredth anniversary of the Graduale Romanum, there is much to celebrate as well as much to regret. Thirty years ago, no one would have thought that chant would be currently undergoing such a revival. But in this area of church music, we need to learn to expect and count on miracles. We are living in the midst of another one. The famously unfulfilled mandate of the Second Vatican Council, that Gregorian chant should enjoy a principal place (principem locum obtineat) in liturgy, is finally being taken more seriously by Catholic musicians and ecclesiastical bodies. But there are many issues that are unresolved, mostly due to the lack of consciousness on the part of musicians and clergy. The Vatican document from 1963 assumed more knowledge than most Catholic musicians and pastors currently have on this issue. For example, people might believe that one way to implement the mandate is to add chant to the hymn selections. The belief persists that if you add one of those into the mix, you are living up to the ideal of the council. There is nothing wrong and much right about this approach if the goal is a transition measure toward actually using chant in the Mass. These chant hymns are a great place to begin. A choral director can easily add one of these at offertory or communion, and invite people to sing. The people will pick them up and learn that Latin is a beautiful language and that chant has a special capacity for lifting the heart and mind toward heaven. But let us be clear that this action alone, as meritorious as it might be, has little to do with what the council envisions, what the General Instruction on the Roman Missal states, or what the new bishops' document on music calls for. There is a big difference between using an old Latin hymn as one in a selection of musical picks for Mass, and actually singing the chants as part of the Mass. The difference is not clear to most people involved in Catholic music. When the Vatican documents speak of Gregorian chant, it is calling to mind the vast and long tradition of chant having nothing to do with popular chant hymns. It is speaking specifically of the chants that are woven into the fabric of the liturgy itself. In short, it is speaking of using the chants that are part of the structure of the Mass. In their order of appearance in the Mass, they are as follows:

There is a Gregorian chant for each of these parts of the Mass. In addition, there are sung parts of the liturgy that might also be considered part of Gregorian chant. That's not to say that chant hymns don't have a place. They certainly do and they are especially appropriate because they follow up on the style and language of the parts of the Mass that are sung according to the Gregorian tradition. Now, at this point in the discussion, many Catholic musicians throw up their hands in despair or disbelief. They have amassed a set of hymnals and resources on their bookshelf, materials they hace accumulated from many years of workshops and mailings from mainstream publishers. Not one of them includes any of what I've mentioned above. How can this music be considered the normative part of Mass if it makes no appearance in the hundreds of materials on my own music shelf — and this after decades as a full-time Catholic musician? The vast gulf that separates legislation from practice has persisted for a very long time, but, as we saw during the pope's visit, this has begun to change. In the same way, Catholic musicians in this country are going to face a great deal of professional pressure to upgrade their knowledge and heighten their ideals. It is a privilege of the highest order to provide music for Mass, and with it comes some intense obligations. Will the musicians who are in a position to make decisions concerning Masses of the future strive to achieve the ideal or will they brush off the ideal and make excuses for not doing what they should do? This is the great question that Catholic musicians must confront in the coming years. |

There is a vast and growing movement of people around the world who have fallen in love once again with chant, and dedicated much of their lives to studying and singing it.

I'm not sure you can say this of any other art that dates from the Apostolic Age.

It is, of course, the same way with the Christian idea itself, the power of which continues to grow even though it is two thousand years old.

Chant too entices us with its beauty and power because it is intimately bound up with the whole history of Christian worship.

No attempt to crush it, belittle it, marginalize it, or reduce it to a mere sign of some class struggle, will finally succeed.

It is the music of Christianity itself, and has staying power for the same reason that the faith itself does.

There is a vast and growing movement of people around the world who have fallen in love once again with chant, and dedicated much of their lives to studying and singing it.

I'm not sure you can say this of any other art that dates from the Apostolic Age.

It is, of course, the same way with the Christian idea itself, the power of which continues to grow even though it is two thousand years old.

Chant too entices us with its beauty and power because it is intimately bound up with the whole history of Christian worship.

No attempt to crush it, belittle it, marginalize it, or reduce it to a mere sign of some class struggle, will finally succeed.

It is the music of Christianity itself, and has staying power for the same reason that the faith itself does.