|

|

| Musical Musings: Miscellaneous |

Is Chant for Everyone?Part 1This article appeared as the first half of the Commentary section in the Summer 2008 edition of Sacred Music journal, published by the Church Music Association of America. It is reprinted with the kind permission of the author, Jeffrey Tucker.

The Vespers service in Washington was an excellent example. The polyphony, sung in the very place where last year's [CMAA] Sacred Music Colloquium was held, was stunning. The psalms were sung in English as set by Fr. Samuel Weber. It was solemn and holy in every way. It was the first major liturgical event of the trip, so many people heard, for the first time, such treasures of the repertoire as Dum transisset sabbatum by John Taverner and Maurice Duruflé's setting of Tu es Petrus. So it was in New York at Saint Patrick's Cathedral, where glorious hymns combined with the compositions of Palestrina, Victoria, Rheinberger, and also antiphons and ordinary chants from the Graduale Romanum. It was even true in the Yankee Stadium Mass, about which expectations were far lower. But even here we heard polyphony by Victoria together with classical music fitting for the occasion. Cardinal Edward Egan told the musicians that "With God as my judge, the first words out of the Holy Father's mouth after Mass were, 'The music here is marvelous.'" I found most impressive the use of Credo III from the Graduale in this large setting. It was of course in Latin. The participation was broad. In this one demonstration we had a refutation of all the usual claims about chant, that it cannot be done in large public venues, the people will not sing, that chant is undemocratic, outmoded, or forgotten. The fact is that people sang, it was glorious and inspiring. Again, the effect of this on Catholic viewers, most of whom have never experienced this in their parishes, is impossible to overestimate. Here we had a vast Catholic congregation of sixty thousand people singing the creed in Latin. All of the musical problems of the last several decades seemed almost not to exist in these settings. The contrast with the past is striking and gladdens the heart. Special credit here goes to Peter Latona, the Director of Music at the National Shrine, to Jennifer Pascual, Director of Music at Saint Patrick's, and also to Guido Marini, Master of Ceremonies for papal liturgies, who worked very hard to have everyone on the ground level focus on the principles and their application. There was, of course, one event that was not like the others: the DC Mass at National Stadium. The people who were there describe the event as life-changing and holy due to the presence of the Holy Father, and the exceptionally well-done altar arrangement, the episodes of silence, among many other aspects of the Mass. Matters were different for those of us who watched on television. The music was predominant over the other aspects. Overall, it not only represented a repudiation of what Benedict XVI has written on music appropriate to Mass, all in the name of "multiculturalism," which in today's civic ethos is primarily a politcal and not a theological idea. Thus did we hear the samba and meringue that supposedly reflect the identity-interests of Hispanics, Southern gospel styles that reflect the identity-interests of African-Americans, wilderness flutes and other strange instruments and styles to appeal to ... I'm not entirely sure, but my point is clear. The overt displays of deference to nearly every tradition of music pushed into the background the central point that we are united in Christ, united in our Catholicism. The Pope, moreover, has written in his book, The Spirit of the Liturgy, that the issue of "multiculturalism" was confronted and dealt with early in Christian history, as the Roman Rite developed to deal with intense diversity of early converts from many regions and language groups. The result was the Latin language of the liturgy, and Gregorian chant and its timeless and universal sound, together with the texts of psalms that speak to universal impulses in the human person. True multiculturalism is achieved in the Roman Rite itself, a point which is still emphasized in church teaching and which was well-illustrated in New York. This is not inaccessible knowledge. The Second Vatican Council stated very plainly that Gregorian chant and polyphony should enjoy primacy of place at Mass. This teaching has been restated by the pope time and again. This is not his personal taste at work, nor mine. Chant is the music of the Mass. Styles that elaborate on chant are also suitable. What the liturgy does not admit are styles that are contrary to the liturgical sense and purpose of reaching outside of ourselves and into eternity.

Without that ideal, what are we left with?

Let the pope answer:

When the liturgy is self-made, however, then it can no longer give us what its proper gift should be: the encounter with the mystery that is not our own product but rather our origin and the source of our life. A renewal of liturgical awareness, a liturgical reconciliation that again recognizes the unity of the history of the liturgy and that understands Vatican II, not as a breach, but as a stage of development: these things are urgently needed for the life of the Church. I am convinced that the crisis in the Church that we are experiencing today is to a large extent due to the disintegration of the liturgy, which at times has even come to be conceived of etsi Deus non daretur: in that it is a matter of indifference whether or not God exists and whether or not he speaks to us and hears us. But when the community of faith, the world-wide unity of the Church and her history, and the mystery of the living Christ are no longer visible in the liturgy, where else, then, is the Church to become visible in her spiritual essence? Then the community is celebrating only itself, an acitivity that is utterly fruitless. And, because the ecclesial community cannot have its origin from itself but emerges as a unity only from the Lord, through faith, such circumstances will inexorably result in a disintegration into sectarian parties of all kinds — partisan opposition within a Church tearing herself apart. This is why we need a new liturgical movement, which will call to life the real heritage of the Second Vatican Council.1 The impulse to divide the Christian community by such factors as ethnicity and background, and to see that those divisions are played out in a liturgical context, driven by the desire to not be stuck with "Euro-centric" music, is not a new one. It dates back decades, and has been invoked against the use of chant. Browsing the archives of Pastoral Music [the NPM journal], for example, I came across a very peculiar piece of writing from February-March 1977, called "Pocahontas Never Sang Gregorian Chant," by Eileen Elizabeth Freeman, then a guitar instructor studying at Notre Dame University. She offers an argument against the need for chant to be pervasive in the Roman Rite in America.

What about the claim that Pocahontas never sang chant? I'm not sure that has anything to do with it. Napoleon probably didn't sing chant either. Had she been a Catholic, she certainly would have heard chant in any mission parish throughout North America at the time, as many scholarly studies have shown. Pocahontas, however, wasn't a Christian at all until she married John Rolfe and was christened Lady Rebecca. I'm supposing they were Anglican, and it seems reasonable to assume that Gregorian chant wasn't commonly sung in the Anglican Church in the United States. When they visited England in 1616, however, it was the Elizabethan era, and the music of Thomas Tallis was still heard in the cathedral. So we might amend the claim to sya that while Pocahontas never sang chant, she might have listened to a live performance of "If Ye Love Me." More seriously, the core of this article's point needs addressing, since it is still the case that people associate chant with all sorts of sociological notions that involve class, background, ethnicity, and race. These days, the demographics and financial analytics do not support the view, at least not in my experience. In today's American Catholic Church, the money and power are almost wholly with institutions engaged in the commercial promotion of contemporary styles. They are the ones with the big corporations and marketing apparatus. Their composers are well paid, their music is expensive and protected by copyright, and they have the connections with people in high places of power and influence. The chant movement today, in contrast, is made up of regular people in parishes, most of whom are not paid a full-time salary, do not have elite educations, and have no high-level connections with anyone. The fact remains that chant is widely regarded as snobbish, and no amount of demographic analysis of who is doing it will change that impresssion. In the same way, however, I suppose we could say that the Pietá reflects a high-level, cultured tastes as does the Sistine Chapel and Gothic cathedrals and all the rest. Certainly these forms of art can be seen as "higher," in some way, than a carved piece of driftwood and a log-cabin worship space. Piety is possible in lower forms of art, but the question is what we want to consider the ideal and whether we are willing to offer the best we have to God. If an artist can carve and paint art that is beautiful and universal, should we put him down and say, "Oh, you must not do that since it might alienate people"? Are we right to say that the "common people" are just too uncouth to understand what is beautiful and glorious? This strikes me as a profoundly insulting way to proceed. We end up pandering to stereotypes, and we saw an example of this in the Nationals Stadium papal Mass in Washington. 1. Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, Milestones: Memories 1927-1977 (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1998), pp. 148-149. Copyright © 2008 Church Music Association of America. Reprinted with permission.

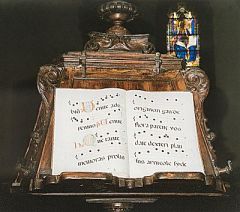

See Graduale Romanum

|

The music at the papal Masses in New York and Vespers at the National Shrine represented impressive progress in the development of Catholic music in America.

Even in these public settings, the practice of liturgical music began to accord with the letter of legislation concerning music, which calls for chant and polyphony to be given primary place.

There can be no doubt that this is due to the influence of Pope Benedict XVI, pressure from the Vatican before the papal visit, the work of so many people to raise the standards in Catholic liturgy, as well as to the changing ethos surrounding music in Catholic liturgy.

The music at the papal Masses in New York and Vespers at the National Shrine represented impressive progress in the development of Catholic music in America.

Even in these public settings, the practice of liturgical music began to accord with the letter of legislation concerning music, which calls for chant and polyphony to be given primary place.

There can be no doubt that this is due to the influence of Pope Benedict XVI, pressure from the Vatican before the papal visit, the work of so many people to raise the standards in Catholic liturgy, as well as to the changing ethos surrounding music in Catholic liturgy.

She argues that "calling chant the traditional music of American Catholicism is a form of religious myth."

Further, "at no time during the formative centuries of plainchant did it ever become a vehicle for congregational song.

Gregorian chant was the almost exclusive prerogative of monastic choirs and cathedral choirs ...

Throughout the Middle Ages, this dual tradition persisted, with Gregorian chant being the music of the 'official' church, the literati (at least in the metaphorical sense!), and vernacular hymns sustaining the faith musically for the average person."

She further says that the same is true of polyphony: music of the elites.

She argues that "calling chant the traditional music of American Catholicism is a form of religious myth."

Further, "at no time during the formative centuries of plainchant did it ever become a vehicle for congregational song.

Gregorian chant was the almost exclusive prerogative of monastic choirs and cathedral choirs ...

Throughout the Middle Ages, this dual tradition persisted, with Gregorian chant being the music of the 'official' church, the literati (at least in the metaphorical sense!), and vernacular hymns sustaining the faith musically for the average person."

She further says that the same is true of polyphony: music of the elites.